Without the Irish, the atmosphere at Old Trafford would be so much the poorer.

Without the Irish, the atmosphere at Old Trafford would be so much the poorer.

The reaction of the local English inhabitants was initially one of hostility and it was in Manchester in 1807 that the first branch of the Grand Order of the Orange Order on mainland Britain was founded to fight the supposed threat from ‘dirty, treacherous , simian, Irish papists’ to the superior white British Protestant civilized way of life. With the Tory Party and aristocratic establishment strongly allied to Orange Unionism, it was not surprising that the Catholic Irish actively flocked to the standards of the Chartists and later the Labour Party who spearheaded the campaign for increased rights for the downtrodden working class. Yet over time the Irish in Britain, while being active in politics, tended to hide their Irish identity as many felt that their advancement in their new homeland would be curtailed if they promoted the cause of Irish nationalism.

The reaction of the local English inhabitants was initially one of hostility and it was in Manchester in 1807 that the first branch of the Grand Order of the Orange Order on mainland Britain was founded to fight the supposed threat from ‘dirty, treacherous , simian, Irish papists’ to the superior white British Protestant civilized way of life. With the Tory Party and aristocratic establishment strongly allied to Orange Unionism, it was not surprising that the Catholic Irish actively flocked to the standards of the Chartists and later the Labour Party who spearheaded the campaign for increased rights for the downtrodden working class. Yet over time the Irish in Britain, while being active in politics, tended to hide their Irish identity as many felt that their advancement in their new homeland would be curtailed if they promoted the cause of Irish nationalism.Ironically this assimilation into English society was promoted by the main organization that the majority of the Irish emigrants trusted, namely the Catholic Church. Though the church did Trojan work looking after the spiritual and social needs of the Irish, many of its native hierarchy wanted to ensure that it maintained its indigenous ambiance and made every effort to have the newcomers become first and foremost ‘English Catholics’. Of course they could not totally kill off support for Irish separatism. In fact it was in this northern city that one of the most famous episodes in Irish republicanism mythology occurred- the Manchester Martyrs. The hanging of 3 Fenians in 1867 for the accidental killing of a policeman during a successful operation to free their leaders from a prison van led to the immortalisation of the words of Edward Meagher Condon one of the prisoners when, after he was sentenced to death by the court, stated "I have nothing to regret, or to retract. I can only say God Save Ireland.”

It was to Manchester that Eamon de Valera, President of Sinn Féin, was taken to stay with Irish republicans amongst the local population after he and others were sprung by the IRA from Lincoln Prison in February 1919 during the War of Independence before secretively returning to Ireland.

So there was always a hard core of dedicated volunteers in the city that promoted Gaelic sports, music, nationalism and traditions in Manchester.

But they were too often swimming against the tide with many wanting to adopt lock, stock and barrel the key characteristics of the majority population. For some, Ireland was too closely identified with poverty, ruralism, backwardness and a lack of modernity. For others it was a sense of bitterness towards Ireland for forcing them to leave family and friends behind to endure a life of loneliness in order to eke out an existence of sorts in a foreign and often hostile land.

Oddly enough, a song written by an English Communist Manchurian of Scottish extraction about a district in Manchester became one of the most famous 'Irish' traditional ballads of all time. Ewan McColl wrote Dirty Old Town about his native Salford. But it secured such international status when it was covered by the Dubliners in the 1960s that its lyrics were deemed to refer to Dublin.

British & 'British Irish' Contribution to the Recent Global Popularity of 'Irishness'

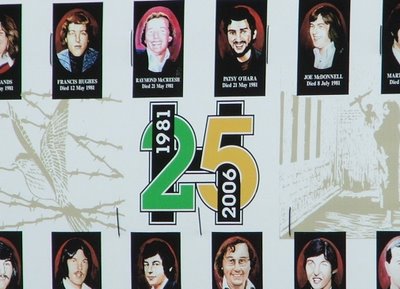

From the early 1980s though, there was a marked revival in Gaelic culture amongst the young Manchester-Irish as a counter-reaction to the demonization of the Irish during the emergence of the ‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland particularly during the period of the Hunger Strikers, the rise of radical Sinn Fein and the harshness of special legislation such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act towards the Catholic Irish community. This was strengthened by the growing global popularity of English-Irish bands with their Celtic sounds such as the Pogues; the Irish soccer team with its English-Irish soccer players (John Aldridge, Mick McCarthy, Andy Townsend etc) led by an Englishman Jack Charlton and the phenomena of the Irish-American inspired Riverdance with its attractive sensual Irish dancing. Yet it was courageous English political activists such as Gareth Pierce, Tony Benn, Clare Short, Chris Mullen and notably Ken Livingstone (from his time as head of the Greater London Council {GLC} onwards) that acted as prime catalysts in the Irish in England, particularly the young and the more recent arrivals, throwing off what seemed to be a self-imposed collective ‘badge of shame’.

Note: Many thanks to the Manchester Irish.com website with its Manchester's Irish Story

Plus! Check out the website for Irish supporters of Manchester United at www.irishreddevils.com